Scientists at the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary have identified why thousands of octopuses migrate to the Davidson Seamount. The discovery highlights the role of geothermal heat in accelerating embryo development in the deep ocean.

TLDR: Researchers have solved the mystery of the “Octopus Garden” off the California coast. By utilizing deep-sea submersibles, the team discovered that geothermal springs significantly speed up the hatching process for thousands of nesting octopuses, revealing a critical link between geological activity and marine reproductive success.

Deep beneath the rolling waves of the Pacific Ocean, approximately 80 miles off the coast of Central California, lies a geological giant known as the Davidson Seamount. This extinct underwater volcano, which rises 7,480 feet from the seafloor, is managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. In recent years, this site has become the focus of intense scientific scrutiny following the discovery of the “Octopus Garden”—the largest known aggregation of deep-sea octopuses on the planet.

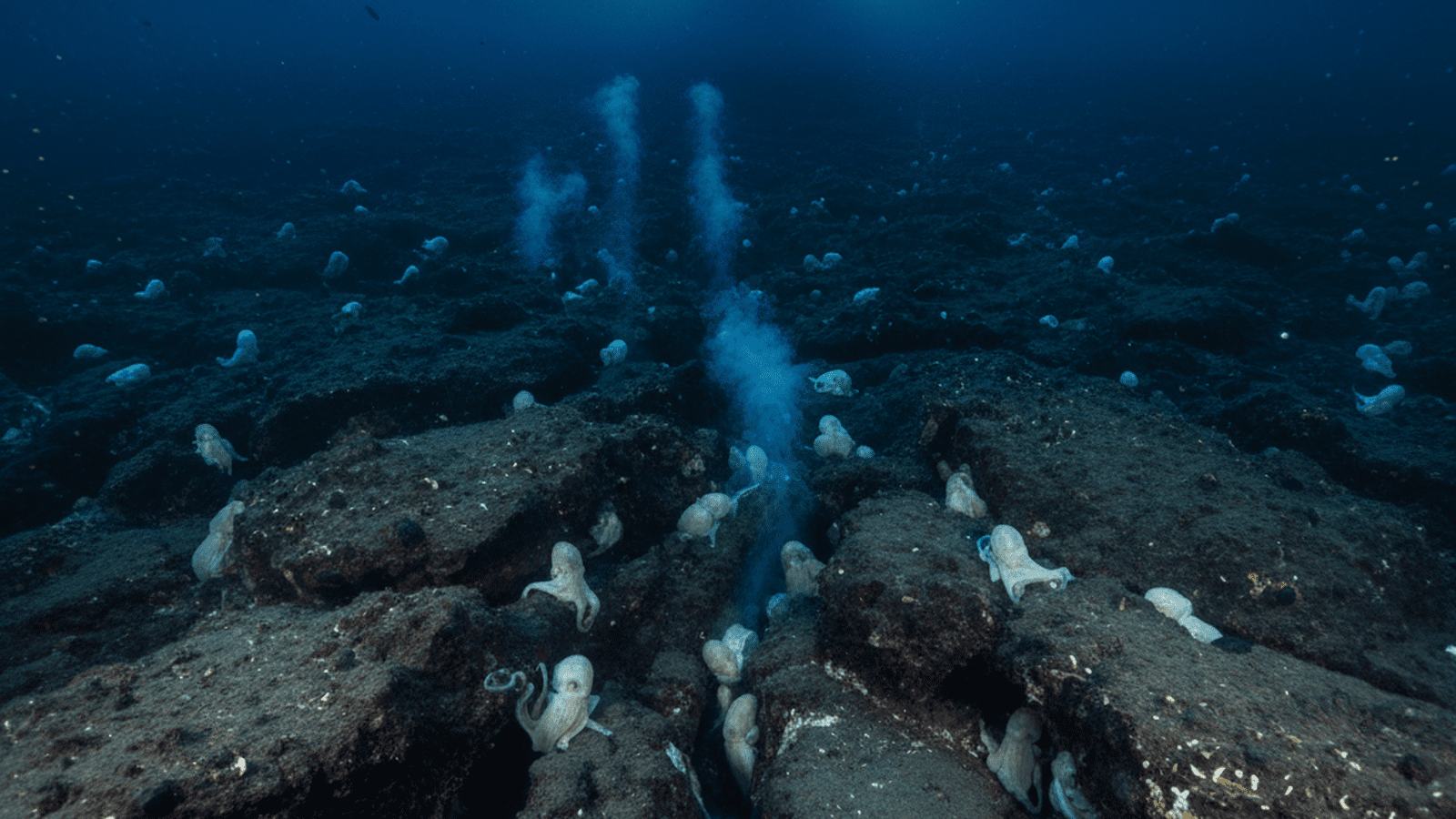

First identified in 2018 by researchers aboard the E/V Nautilus, the site initially presented a baffling scene: thousands of pearly-white octopuses, specifically the species Muusoctopus robustus, were seen huddled in the dark, basaltic crevices of the seamount. The sheer density of the population—estimated at over 20,000 individuals—was unprecedented for the deep sea, where food is scarce and life typically exists in isolation. For years, the biological driver behind this massive gathering remained a subject of intense speculation, with scientists wondering why these creatures would choose such a specific location for their nursery.

To solve the mystery, a collaborative team from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), NOAA, and several other institutions launched a series of expeditions using the advanced remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Doc Ricketts. Over the course of three years and 14 separate dives, the team utilized high-definition cameras and precision sensors to monitor the site. They discovered that the octopuses were not randomly distributed; they were specifically clustered around hydrothermal springs where relatively warm water seeps through the seafloor cracks.

In the abyss, where temperatures hover around a bone-chilling 1.6 degrees Celsius (35 degrees Fahrenheit), metabolic processes occur at a glacial pace. For most deep-sea cephalopods, the incubation period for eggs is an arduous marathon that can last several years—in some species, up to a decade. However, the thermal sensors deployed by the ROV revealed a startling temperature differential. Inside the nesting crevices, the water temperature rose to as high as 11 degrees Celsius (51 degrees Fahrenheit). This localized geothermal warmth acts as a biological catalyst, significantly accelerating the development of the embryos.

The research, recently published in Science Advances, confirms that by nesting in these “hot spots,” the pearl octopuses reduce their incubation period to approximately 1.8 years. This is a critical evolutionary advantage. A shorter brooding period drastically reduces the window of vulnerability during which the eggs are susceptible to predation by deep-sea scavengers like snails, shrimp, and anemones. In the harsh environment of the deep ocean, every month shaved off the development cycle increases the probability of survival for the next generation.

Furthermore, the shortened timeframe is essential for the survival of the species because of the extreme physical toll on the mothers. Like many octopus species, Muusoctopus robustus is semelparous, meaning they reproduce only once before dying. During the brooding period, the mothers do not feed, instead dedicating all their remaining energy to guarding and aerating their egg clutches. By utilizing geothermal heat, the mothers ensure their offspring hatch before the parent succumbs to exhaustion. This discovery underscores the vital importance of seamounts as biological hotspots. These underwater mountains provide unique chemical and thermal environments that support life in the otherwise desolate deep-ocean plains. As deep-sea mining and climate change pose increasing threats to the ocean floor, the protection of sites like the Davidson Seamount becomes paramount for marine conservation.