In 1996, the United States Congress passed the Line Item Veto Act, granting the President the power to strike specific provisions from legislation. This significant expansion of executive power was ultimately struck down by the Supreme Court in 1998 for violating the Presentment Clause of the Constitution.

TLDR: The Line Item Veto Act of 1996 briefly granted U.S. Presidents the authority to cancel specific spending items within larger bills. Intended to reduce federal deficits, the law was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, which ruled that the President cannot unilaterally amend legislation passed by Congress.

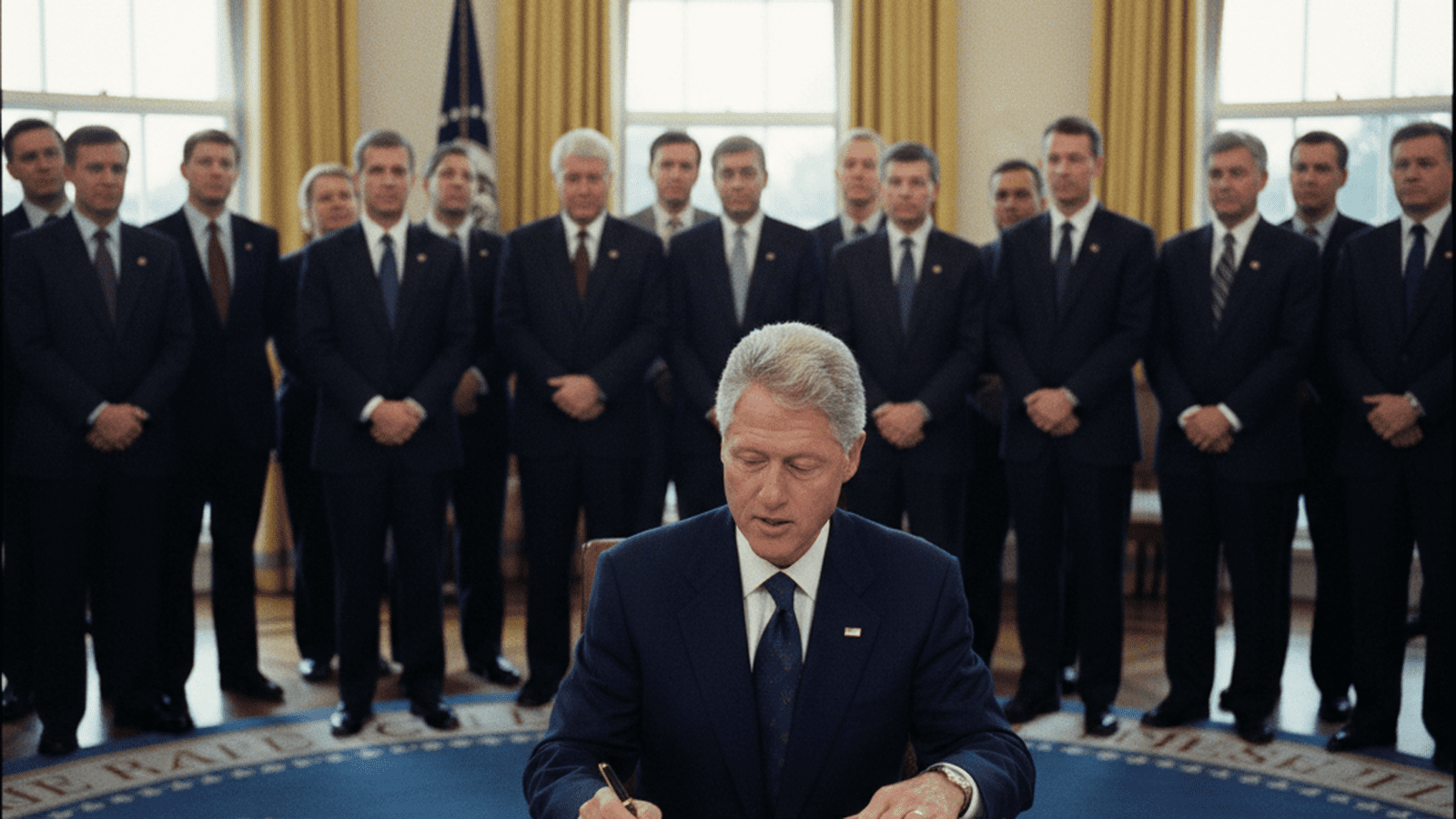

The passage of the Line Item Veto Act of 1996 marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of executive power within the United States federal government. For decades, proponents of fiscal conservatism had argued that the President required a mechanism to eliminate wasteful spending without rejecting entire appropriations bills. This movement gained significant momentum during the 104th Congress, fueled by the Republican Party’s Contract with America platform. President Bill Clinton, seeking common ground with a newly empowered opposition legislature, signed the measure into law on April 9, 1996, in a ceremony that promised a new era of fiscal discipline.

The Act fundamentally altered the legislative process by allowing the President to cancel three specific types of provisions within a signed law. These included any dollar amount of discretionary budget authority, any item of new direct spending, or any limited tax benefit. Under the new rules, the President could sign a bill and then send a special message to Congress within five days identifying the items to be struck. These cancellations would take effect immediately unless Congress passed a disapproval bill to reinstate them, which the President could then veto. This structure effectively shifted the burden of legislative consensus from the executive to the legislative branch.

Supporters argued that the line-item veto was a necessary tool for maintaining fiscal responsibility in an era of rising deficits. They pointed to the tendency of lawmakers to attach localized projects, often called pork barrel spending, to essential national funding bills. By granting the executive the power to prune these additions, advocates believed the federal budget could be managed with greater precision. However, critics warned that the law granted the President an unconstitutional role in the lawmaking process, essentially allowing the executive to rewrite legislation after it had been passed by both houses.

The legal challenges to the Act began almost immediately after its implementation. A group of senators, led by Robert Byrd of West Virginia, filed an initial suit arguing that the law diluted their legislative authority. While the first challenge was dismissed for lack of standing, a subsequent case reached the Supreme Court after President Clinton used the power to cancel provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. The City of New York and several healthcare providers challenged the cancellation of a provision that would have waived certain tax liabilities for New York State, arguing the President had exceeded his constitutional bounds.

In the 1998 landmark case Clinton v. City of New York, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that the Line Item Veto Act was unconstitutional. Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the majority, explained that the law violated the Presentment Clause of Article I. The Court held that the Constitution outlines a specific procedure for enacting laws, and that procedure does not permit the President to amend or repeal portions of statutes. Stevens noted that there is no provision in the Constitution that authorizes the President to enact, to amend, or to repeal statutes, regardless of the fiscal benefits such a power might provide.

The ruling restored the traditional veto power, requiring the President to either sign or return a bill in its entirety. While the Line Item Veto Act was short-lived, it highlighted the ongoing tension between the branches of government over budgetary control and executive reach. In the years following the decision, various expedited rescission proposals have been introduced in Congress to achieve similar fiscal goals within constitutional bounds. These efforts reflect a persistent desire to refine the executive’s role in the federal budget process while respecting the separation of powers established by the founders.