Researchers have discovered that mineral nodules on the deep-ocean floor produce oxygen through electrolysis, a process occurring without sunlight. This “dark oxygen” production challenges the scientific consensus that photosynthesis is the sole primary source of Earth’s oxygen.

TLDR: Scientists found that polymetallic nodules in the Pacific Ocean generate electricity to split water molecules, creating oxygen in total darkness. This discovery suggests that deep-sea mining could disrupt vital oxygen sources for abyssal life and shifts our understanding of how oxygenated environments first formed on Earth.

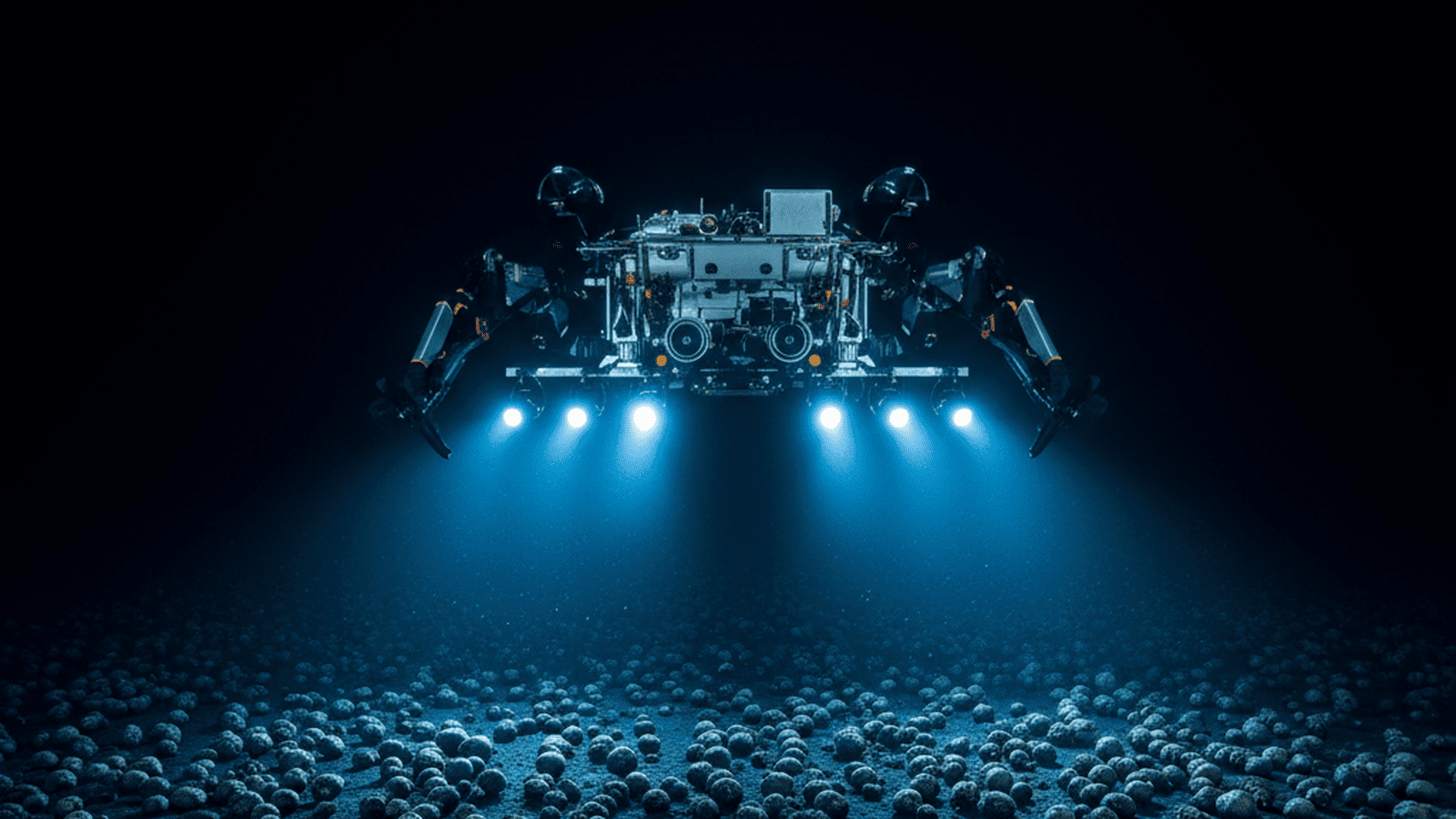

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is a vast, abyssal plain stretching across the Pacific Ocean, characterized by its extreme depth and total absence of sunlight. It was here that a team of international researchers, led by Professor Andrew Sweetman of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS), made a discovery that has sent shockwaves through the scientific community. At depths of approximately 4,000 meters, they identified a process where oxygen is being produced on the seafloor without the aid of photosynthesis. This “dark oxygen” phenomenon suggests that the life-sustaining gas can be generated through purely geochemical means, challenging the long-held belief that sunlight is a prerequisite for significant oxygen production on Earth.

The discovery was not immediate but rather the result of persistent observation and skepticism. During field research, the team deployed benthic chambers—sophisticated, automated laboratories that seal off sections of the seafloor to monitor biological activity. Typically, these chambers measure the rate at which deep-sea organisms consume oxygen. However, the sensors consistently recorded oxygen levels rising rather than falling. Initially, Sweetman and his colleagues suspected the equipment was malfunctioning or that oxygen was leaking into the chambers from the surface. It was only after multiple expeditions and the use of independent sensor technologies that the team accepted the data: the seafloor itself was producing oxygen.

The source of this oxygen was traced to polymetallic nodules—potato-sized mineral deposits that litter the CCZ. These nodules are rich in metals such as manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper, which are essential components for modern battery technology. The researchers discovered that these nodules act as “geobatteries.” By placing tiny electrodes on the surfaces of the nodules, they measured an electrical potential of up to 0.95 volts. When these nodules are clustered together, the voltages can sum up, easily exceeding the 1.5-volt threshold required for the electrolysis of seawater. This process splits water molecules (H2O) into hydrogen and oxygen gas, providing a steady supply of “dark oxygen” to the surrounding environment.

This finding has profound implications for our understanding of Earth’s history. For decades, the Great Oxidation Event, which occurred roughly 2.4 billion years ago, was attributed solely to the emergence of photosynthetic cyanobacteria. The realization that a non-biological source of oxygen exists suggests that aerobic life might have had a foothold on Earth much earlier than previously thought, potentially evolving in the dark recesses of the ocean floor before migrating to the surface. It forces a re-evaluation of the conditions necessary for the origin of life.

Furthermore, the discovery adds a layer of complexity to the debate over deep-sea mining. The CCZ is currently the primary target for mining companies looking to extract minerals for electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy infrastructure. If these nodules are not just passive rocks but active components of the abyssal ecosystem’s life-support system, their removal could be catastrophic. Scientists warn that mining could effectively “unplug” the oxygen supply for deep-sea organisms, leading to localized extinctions and the collapse of fragile ecosystems that have remained stable for millions of years.

Beyond our planet, the implications extend to astrobiology. Icy moons in our solar system, such as Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Enceladus, are believed to possess liquid water oceans beneath their frozen crusts. If similar electrolytic processes occur on those distant seafloors, these moons could harbor oxygenated environments capable of supporting complex life, even in the absence of solar radiation. As researchers continue to investigate the global scale of this phenomenon, the discovery of dark oxygen serves as a reminder of how much remains to be learned about the hidden depths of our own world.