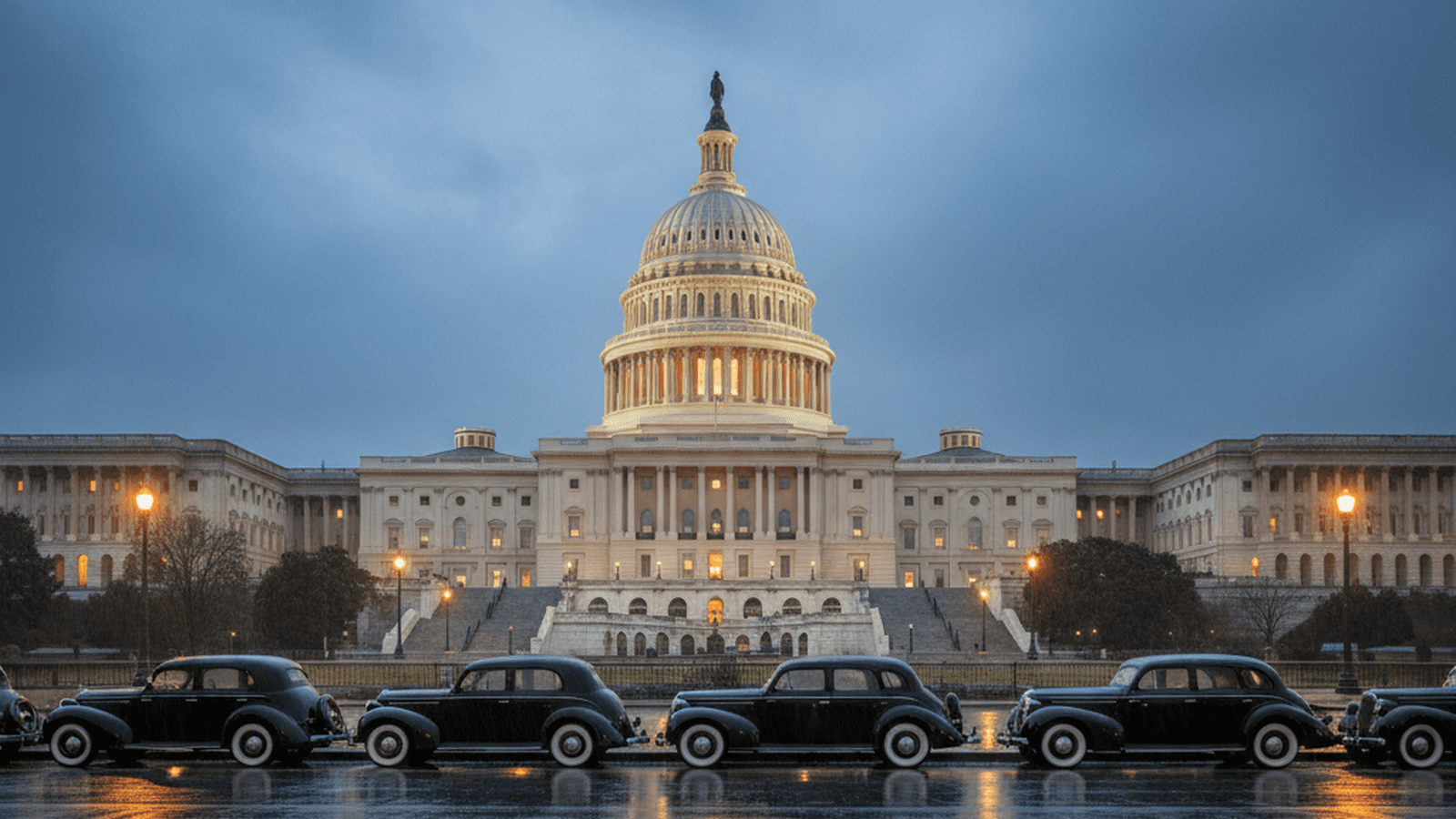

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill to expand the Supreme Court and protect New Deal legislation. The resulting political firestorm in the United States led to the formation of a powerful conservative coalition in Congress that resisted further executive expansion.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt entered his second term in 1937 with a massive electoral mandate and a growing frustration with the federal judiciary. The Supreme Court of the United States had recently invalidated several cornerstones of the New Deal, including the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act. These rulings threatened the administration’s efforts to combat the Great Depression through federal intervention. Roosevelt believed the aging conservative justices on the bench were ideologically committed to an outdated view of the Constitution that prohibited modern economic regulation.

In February 1937, Roosevelt stunned Congress by introducing the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill. The legislation proposed that the president be allowed to appoint an additional justice for every sitting member of the Court over the age of 70, up to a maximum of six new seats. While the administration framed the bill as a measure to improve judicial efficiency and assist elderly judges with their workloads, the political intent was transparent. The goal was to create a pro-New Deal majority that would cease blocking executive and legislative actions.

The reaction to the proposal was swift and overwhelmingly negative across much of the political spectrum. Critics immediately branded the initiative as a court-packing scheme that undermined the independence of the judiciary. Even within the Democratic Party, which held overwhelming majorities in both chambers, the plan caused a deep rift. Many legislators who had previously supported Roosevelt’s economic policies viewed the bill as a dangerous overreach of executive authority that threatened the separation of powers.

This legislative struggle triggered a significant parliamentary realignment within the United States government. Southern Democrats, who were increasingly wary of federal power, began to distance themselves from the White House. They found common ground with the Republican minority, forming an informal but powerful Conservative Coalition. This alliance sought to halt the expansion of the New Deal and protect the traditional prerogatives of the legislative and judicial branches against executive encroachment.

The bill’s momentum stalled further when the Supreme Court itself began to shift its stance. In a move famously dubbed the switch in time that saved nine, Justice Owen Roberts joined the liberal wing to uphold the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act. With the immediate threat to New Deal programs neutralized by the Court’s own actions, the necessity for the reform bill evaporated. The Senate Judiciary Committee eventually issued a scathing report, and the full Senate voted to recommit the bill, effectively killing it.

The failure of the 1937 court-packing plan left a lasting mark on American political history. It demonstrated the resilience of the separation of powers and the public’s deep-seated respect for the Supreme Court as an institution. The Conservative Coalition that emerged during the fight remained a dominant force in Congress until the mid-1960s, successfully blocking many subsequent liberal initiatives. This period of realignment ensured that future attempts to alter the structure of the federal courts would face immense scrutiny and bipartisan resistance.